The following information is summarized in the Two Strategies of Digestion in Hoofed Mammals chart for teachers. Consider printing out a copy of this Teacher Reference Sheet for yourself to refer to as you read!

The purpose of the digestive system is to break food into particles small enough to pass through the gut to enter the bloodstream, which transports these nutrients to all the cells in the body. The basic components of the vertebrate digestive tract often serve similar purposes in diverse creatures, from fish to mammals. Yet, depending on an animal’s feeding behavior, regions used for the transport, storage, and processing of food have evolved specializations. These organs have adapted to be more efficient when digesting and absorbing nutrients from a particular diet.

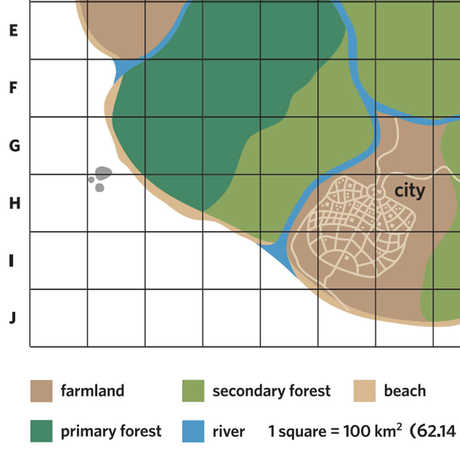

This lesson compares the digestive systems of two herbivores feeding together on the fibrous, nutrient-poor grasses of the African savanna: a buffalo and a zebra. Because grass contains less usable energy than other plant parts such as fruits or nuts, these grazers need to spend a relatively large portion of their day chewing and digesting food to obtain sufficient energy. To reach the nutrients available in the body of a plant cell, the cellulose-rich cell wall must be broken. No vertebrate has the necessary chemicals to digest cellulose in order to capture the energy stored in this complex sugar. Instead, the mammalian digestive tract harbors symbiotic microbes that perform the digestive work, releasing simpler, absorbable molecules.

A buffalo, being a ruminant like antelope, sheep, and goats, chews grass only briefly before swallowing it for the first time. This material travels to the rumen (hence “ruminant”), the largest chamber in its four-part stomach. It is here where bacteria specialized to digest cellulose live and reproduce, digesting cellulose as the rumen churns. With the help of the muscle in the second stomach compartment, the ruminant periodically regurgitates wads of coarser material to be re-chewed, physically preparing the tough plant walls for subsequent chemical digestion by bacteria. Ruminants tend to chew their cud while resting rather than while grazing; a dairy cow might devote 6-8 hours of the day ruminating in sporadic 30 minute sessions. Antelopes often ruminate during the hottest parts of the day, when they would rather hang out in the shade. Rechewed cud is swallowed to return to the digestion vat in the rumen. End products move through the third and fourth stomach sections, responsible for further digestion and absorption; note that in many species, 60-75% of the plant matter has been broken down prior to touching the mammal’s own gastric juices! Because ruminants like buffalo have bacteria working upstream, they maximize the amount of nutrients absorbed later in the small intestine.

Zebras, by contrast, are non-ruminants, so plant matter passes through their system in one fell swoop. Their single, relatively small stomach necessitates several small meals a day. Much like in humans, stomach juices begin to digest protein, but the function of the stomach is mostly temporary storage. From there food is pushed to the small intestine, where the majority of starch, protein, fat, and vitamins are digested in a complex mixture of chemicals. However, recall that the zebra cannot digest cellulose. Although the small intestine is the principal organ of absorption, because bacteria have yet to digest the plant cell walls, many nutrients get passed along. This fibrous feed then enters an enlarged cecum, a pouch-like structure connecting the small and large intestines. Notice that the entrance and exit to the cecum is at the top of the organ, so that it resembles a sack rather than a tube. This equivalent to the rumen of a ruminant is the site for bacterial digestion in a non-ruminant. The nutrients from cellulose digestion are absorbed into the zebra’s blood next via the walls of the large intestine. But remember, the role of the large intestine is mostly to reabsorb the water used during digestion to recycle it in the body; this action also packs the indigestible matter into convenient balls to be eliminated.

Overall, the rougher fiber passing through the non-ruminant’s system results in a lower potential for acquiring nutrients; as such, the zebra compensates by eating more grass, and at a quicker rate. For example, a domestic horse weighing 1000 lbs must eat 2.5-3% of its bodyweight daily; that amounts to 25-30 lbs of grass each day! Although it may seem that non-ruminants (zebras) get the short end of the stick, because they are able to digest low-quality, fibrous grasses, they can survive in habitats lacking the higher-quality shoots, roots, and leaves preferred by ruminants.