Science News

A Colorful Past

February 19, 2014

by Molly Michelson

When did life on Earth become bright and colorful? And how did color changes affect the evolution of different organisms?

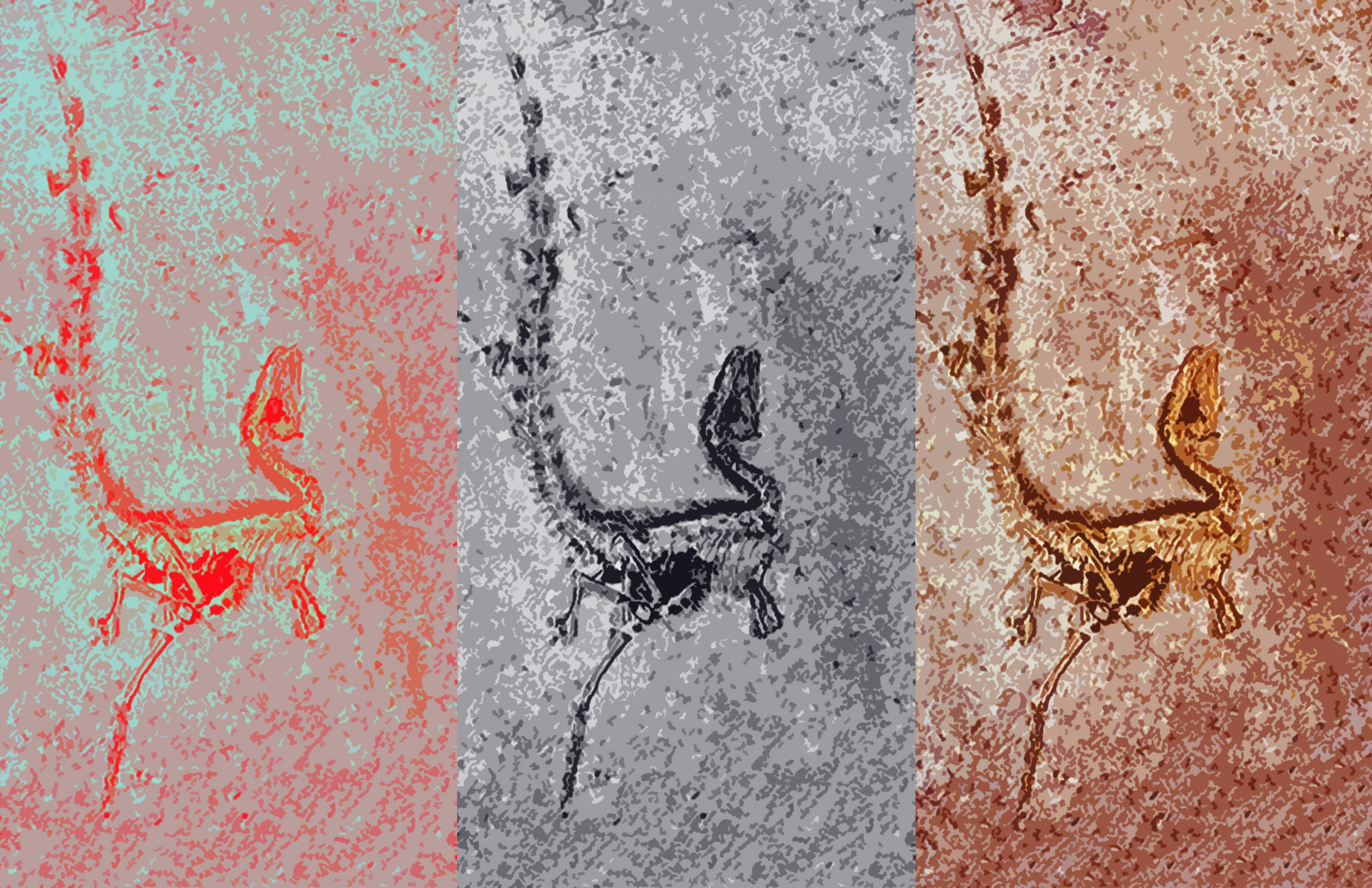

The answers to these questions seem to lie in melanosomes, cells within our bodies that hold melanin, the most common light-absorbing pigment found in animals. For the past several years, scientists have used melanosomes from fossils to determine the coloring of several extinct species of feathered dinosaurs.

A team of international researchers wondered how these melanosomes changed as animals evolved on Earth, so they dug more deeply into these structures. Looking at 181 living species and 13 fossil species, the team reviewed the diversity of shapes and sizes of melanosomes. Overall, the researchers found that living turtles, lizards, and crocodiles, which are ectothermic (cold-blooded), show much less diversity in the shape of melanosomes than birds and mammals, which are endothermic (warm-blooded, with higher metabolic rates).

The team also discovered that the lower diversity holds true for fossil dinosaurs with fuzzy coverings that scientists have described as "protofeathers" or "pycnofibers." In these specimens, melanosome shape is restricted to spherical forms like those in modern reptiles.

By contrast, in the dinosaur lineage leading to birds, known as maniraptoran, the researchers found an explosion in the diversity of melanosome shape and size that appears to correlate to an explosion of color within these groups. The shift in diversity took place abruptly, near the origin of longer, “pinnate” feathers.

“This points to a profound change at a pretty discrete point,” says Julia Clarke of the University of Texas at Austin. “We’re seeing an explosion of melanosome diversity right before the origin of flight associated with the origin of feathers.”

The team was quite surprised to discover that patterns of melanosome diversity found in the feathers of ancient maniraptoran dinosaurs and living birds were similar to those found in mammal hair, as well.

In addition to pigment, melanin also contributes to metabolism, reproduction, and feeding. Because of this, note the researchers, the evolution of diverse melanosome shapes might be linked to larger changes in energetics and physiology.

“We are far from understanding the exact nature of the shift that may have occurred,” says Clarke. “But if changes in genes involved in both coloration and other aspects of physiology explain the pattern we see, these precede flight and arise close to the origin of feathers.

“What is interesting is that trying to get at color in extinct animals may have just started to give us some insights into changes in the physiology of dinosaurs.”

The study was published last week in Nature.