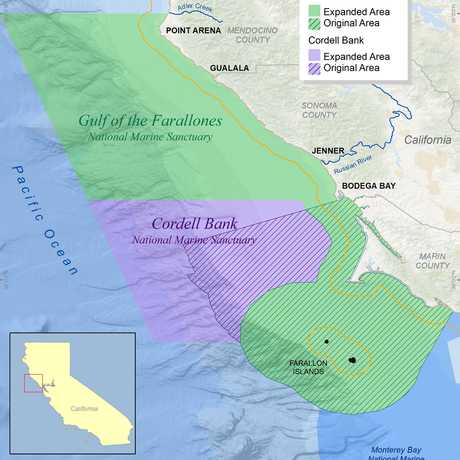

One of the world’s most productive ocean ecosystems sits just outside the Academy’s back door, off California's west coast. It's home to 36 marine mammal species, countless seabirds, and some 25 endangered or threatened species. Part of this area has been protected for decades, since the establishment of the Greater Farallones National Marine Sanctuary (formerly Gulf of the Farallones) in 1981 and the Cordell Bank National Marine Sanctuary just to the north in 1989, but pressure to exploit resources just beyond their boundaries is ongoing.

To ensure the continued protection of this ecologically important region, especially from the oil and gas industry, which had expressed heightened interest in offshore drilling, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA) proposed the expansion of the existing reserves. To bolster their arguments about the vital role this area plays and the unique conditions and organisms that make it special, the agency invited a team of scientists—including the Academy’s Gary Williams, a coral specialist—on several research trips to survey as-yet unexplored parts of the ocean floor in the area.

In March 2015, as a result of this work and the research team's extraordinary findings, NOAA expanded the two sanctuaries by 2,700 square miles, more than doubling the area previously covered. The expansion, and its new regulations, went into effect on June 9, 2015.

Priceless Production Zone

The expansion extends from Mendocino County’s Point Arena southeast to Bodega Bay, where it joins the area covered by the two original sanctuaries. It also stretches far to the west, protecting waters much farther out to sea and helping to ensure the continuation of the nutrient-rich upwelling that makes this part of the Pacific Ocean so productive.

The upwelling begins with powerful offshore currents that push water eastward toward California's west coast. When these currents reach the continental shelf and submerged seamounts surrounding the Farallon Islands and Cordell Bank, cold nutrient-rich water from the deep ocean is pushed up toward the surface. The nutrients propelled upward serve as the foundation for this entire ecosystem.

They support the wide range of sea life that lives in these waters by providing food for fish, which in turn feed the marine mammals and seabirds that rely on this energy source during migrations or nesting. Any disturbance to the influx of nutrients to the area has the potential to affect the entire population that depends on them. To prevent this, the rules of the expansion also protect the area from oil drilling, mining, and ship discharges.

Octocorals in the Deep

Gary Williams, Curator of Invertebrate Zoology at the Academy, has discovered more than 100 species of corals during his career, so finding yet another one, 600 feet deep in what is now the Greater Farallones National Marine Sanctuary, might have just seemed like another proverbial feather in his cap. But his discovery also turned out to be a critical data point in the NOAA team's assessment.

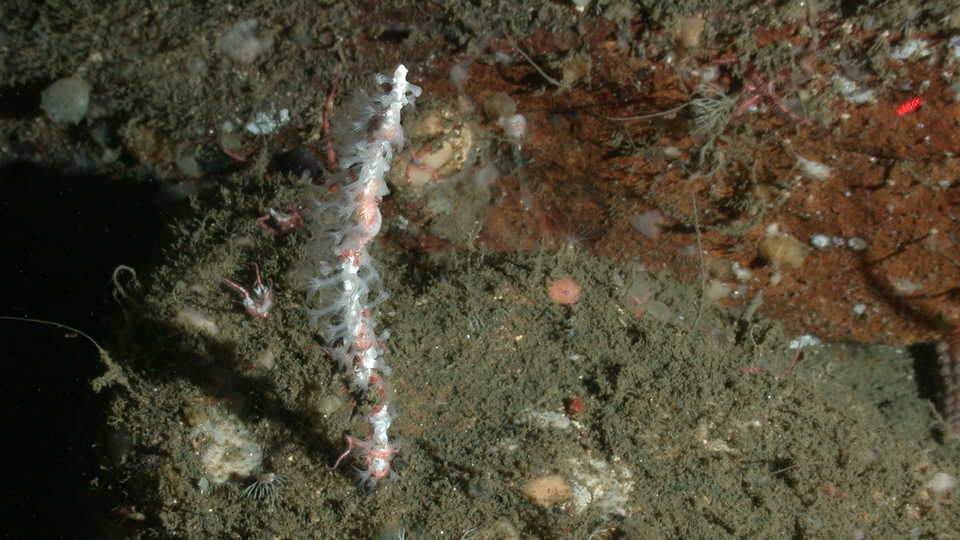

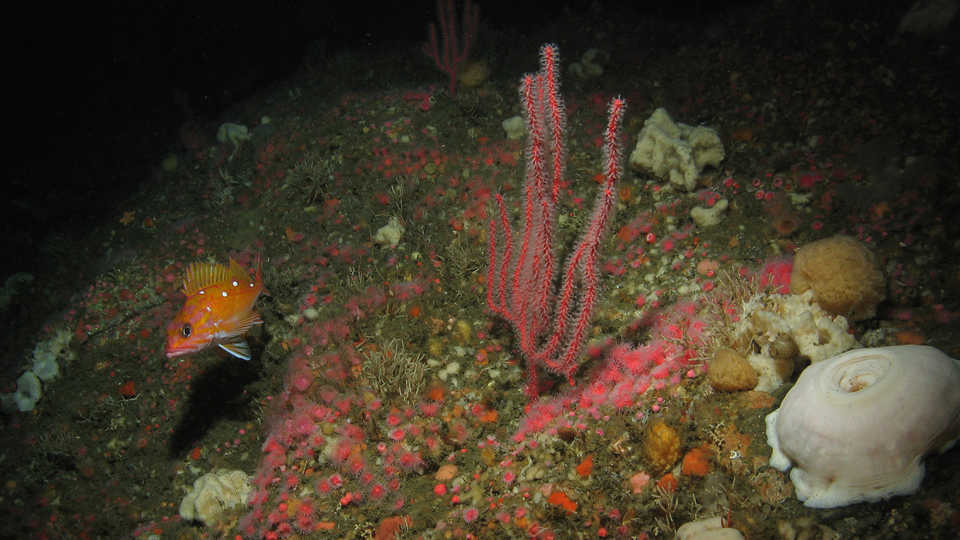

Williams, an expert on octocorals, coral reefs, and deep-sea corals, accompanied two NOAA-led biodiversity surveys in the region in 2012 and 2014. He and the team used remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) tethered to the research vessel to collect specimens and take photographs of ocean life reaching 1,400 feet deep.

While exploring one of the areas, Williams spotted a gorgonian, or sea whip, coral that looked out of place in the rocky habitat he was surveying. He used the ROV’s “claw” to collect a sample to take back to the lab for analysis. Although he recognized the coral as belonging to the Leptogorgia genus, after comparing his new sample to other coral varieties, he determined that what he had found was indeed a new species.

The research team also documented dozens of other deep-water corals and sponges that provide valuable habitat for other types of organisms. Understanding the scope of the region’s communities is crucial to knowing how best to manage and protect the ocean. Williams said, “If you want to protect fisheries, which is what NOAA does, you want to protect the deep sea coral reefs as well.”