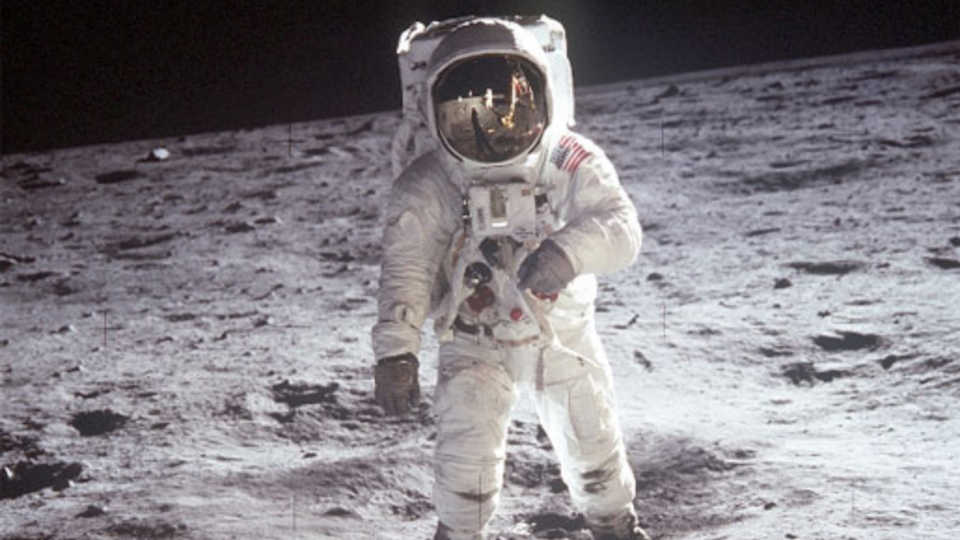

With NASA’s recent refocus on going “back to the Moon” and renewed talks of NASA’s plans to put humans on Mars, I want to remind everyone why we don’t currently live on the Moon: Earth is better and also humans are terrible astronauts and should really only be used as a last resort.

“What?” you’re asking.

Humans are great at a lot of things. We do things that no other animals could ever do, like make art, build buildings, propagate culture, work agriculture, diagnose disease, and about a billion other things that make us truly unique as a species. While we’re not the only species that has spent time in space, we are the only one that intended to, and we’re certainly the most scientifically productive once we get up there. But we aren’t just competing with other animals. Like every other task humans pride themselves on being good at, robots just do it better. Exploring space is no exception.

Take, for example, the logistics of transporting a robot astronaut versus a human astronaut. The Curiosity rover is roughly the size of a SUV, but was shipped compacted to about the size of a Mini-Cooper. A human takes up less space, but needs a much bigger shipping container, and can’t be compressed at all for shipping. Curiosity uses more fuel than any other robotic explorer currently active, consuming around 10 pounds of radioactive material (producing the same mass of waste) over the course of fourteen years. Humans will do that in about a week.

In addition to an unreasonable amount of fuel, humans also need oxygen—and need it to be mixed with other gases so we can breathe it safely. Oxygen is explosive and corrosive, and packing nitrogen in addition to oxygen is inefficient. If we recycle our gases (which we would), that’s another energy cost that must be accounted for.

And this is just the tip of the iceberg in terms of logistics. Robots don’t use fuel while they’re en route, so trips can be optimized without time constraints (a robot doesn’t care if its trip takes six months or six years). Robots can withstand much higher accelerations and decelerations than humans.

That used to be where a robot’s advantages ended. Humans were better at doing science, more adaptable, and more responsive, but that’s quickly changing. With the advances made in self-driving vehicles and integrated tools, a rover such as Curiosity can do any number of things at once, whereas a human can only really focus on a single experiment at a time. And with onboard computers able to adjust for moment-to-moment stimulus, they’re outpacing our last advantage—in-situ decision making. Also time is on their side.

Robots don’t need a return trip. They can just keep going until they run out of fuel. Opportunity lasted 15 years, when its original mission was only for a few months. That’s a triumphant story! Replace “Opportunity” with “Doctor Astronaut” and suddenly that article takes a much darker turn—a fifteen-year mission cut short by an unforeseen planetary event is unacceptable for a human astronaut.

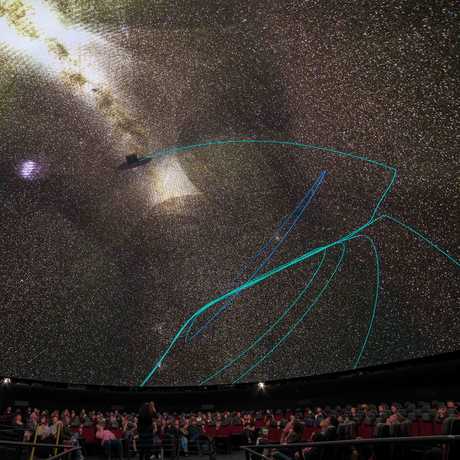

The question I always get from visitors is, “Why haven’t we gone back?” But the question should actually be, “Why would we send humans ever again?”

The answer to that one is easy: Because we want to. And that’s more than enough to make it worth the trip.