The Academy is working to regenerate the natural world. See where we're making a difference.

Between 1999 and 2000, more than 600 gray whales washed up on the West Coast during their annual migration between Baja California and Alaska, prompting the US government to declare the die-off an unusual mortality event (UME) and launch a formal investigation into the cause. Due to the suddenness and unprecedented scale of the event, however, only two of the whales received necropsies. The rest were disposed of or left for the ocean to reclaim, resulting in the loss of crucial data that could have been used to better understand their untimely deaths.

While UMEs are devastating in their own right, it’s what we don’t see that reveals the true extent of the crisis: It’s estimated that stranded whales only represent between 4 to 13 percent of whale deaths in a given year. The remaining majority either sink to the bottom of the ocean or are preyed upon by other species.

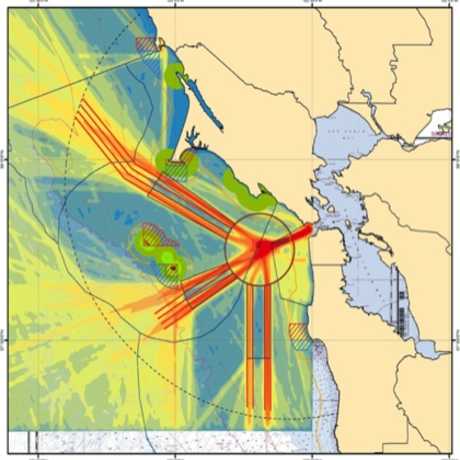

So, when another UME occurred in the summer of 2019, and more than 200 gray whales washed ashore along their migration route, the Academy and its collaborators all along the West Coast were ready. This time, nearly all of the 14 carcasses that beached in the Bay Area were necropsied, providing key data and insights into the increased morbidity.

“Each necropsy tells a story,” says Moe Flannery, the Academy’s Ornithology and Mammalogy collection manager and one of three California state coordinators leading the investigation into the recent UME. “Without the data we gather, researchers wouldn’t have the tools they need to understand why these animals are dying.”

After investigating nearly 700 whale carcasses between 2019 and the end of 2023, scientists found that the leading causes of death were malnutrition and vessel strikes. Previously collected data from the Academy and the MMSN has helped influence legislation seeking to protect vulnerable marine mammal populations, so the hope is that these more recent findings might do the same.